There was a new kind of trouble recently at Kanye West’s and Kim Kardashian’s Hollywood Hills home: a drone hovered above the pool while their daughter was learning to swim. Drones are gaining in popularity, but why would anyone bother sending a drone into the air above my, your, or anyone else’s place? The thing with drones is that they respond to a deeply rooted desire we’ve all had: not just to fly, not just to spy, but to do both things at the same time.

Of course the idea of flying, or at least of building an object that flies, is pretty old. The Chinese invented the bamboo-copter, which was simply a stick with a propeller at the top, around 400 BCE. The idea of mapping things, which usually implies some sort of elevated viewpoint, goes back even further into the depths of human history. But the modern Western obsession with looking at particular places from an elevated viewpoint and putting them on carefully construed maps seems to have emerged at a more recent moment, in the late 1400s.

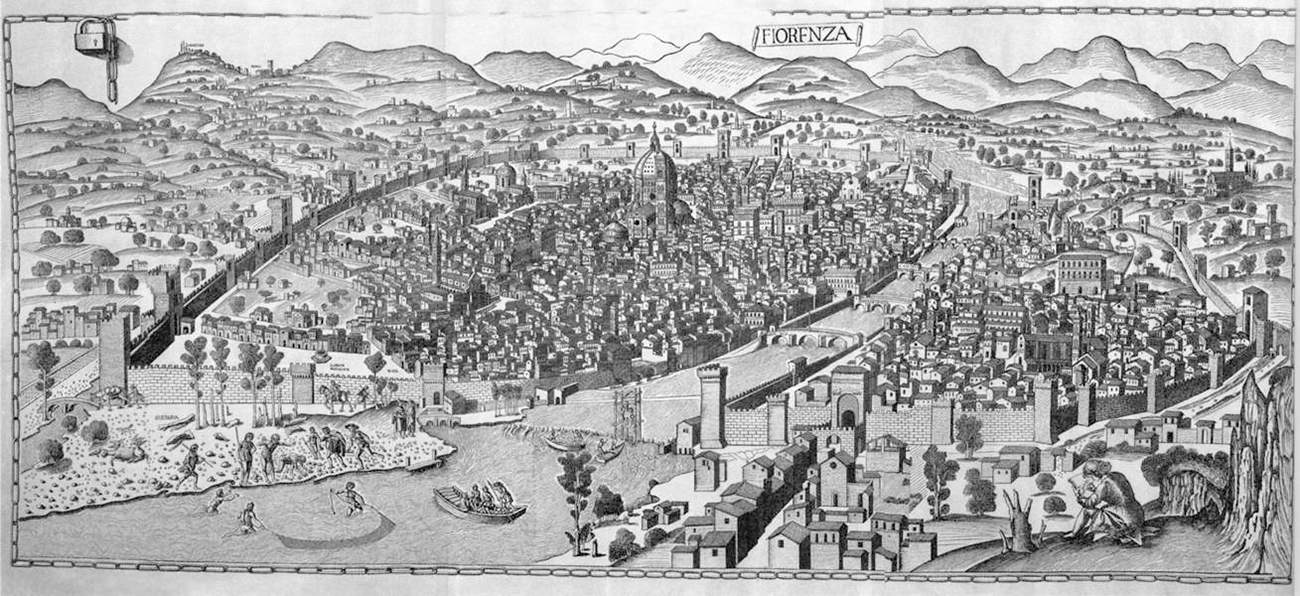

1. Francesco Rosselli, View of Florence with the Chain, 1480s. Woodcut. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence

1. Francesco Rosselli, View of Florence with the Chain, 1480s. Woodcut. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence

That was the time when, in paintings, drawings and prints showing the likeness of European cities, the eye of the observer started to go up higher and higher into the sky. A famous vista of Florence by Francesco Rosselli, produced sometime between 1471 and 1482, shows the city as seen from a hillside [image 1]. The dome is there in the middle of the town traversed by a serene river and surrounded by the beautiful Tuscan landscape. It doesn’t matter that the viewpoint as such doesn’t exist in reality. The artist has been placed in the lower right corner of the image, where he takes in the view and puts it on paper. His presence reassures us, it tells us: this is an image you can trust.

Roughly two decades later, in 1502, Leonardo da Vinci produced a view of the city of Imola that was even more radical [image 2]. Here, the eye of the observer sits vertically above Imola, and what we see is, in essence, a groundplan. The kind of groundplan that we, today, would recognize as a typical city map. Like so much else that Leonardo did, this was an impressive feat. And yet the vista was a flop.

2. Leonardo da Vinci, A Plan of Imola, 1502. Pen and ink over black chalk. Royal Collection Trust, UK

2. Leonardo da Vinci, A Plan of Imola, 1502. Pen and ink over black chalk. Royal Collection Trust, UK

Why? Well, the Renaissance was a time of great developments in portraiture. Cities, like their inhabitants, wanted their picture to be taken, and taken out into the world. At Imola, Leonardo may have proven his genius as a mapmaker, but ultimately people found the result of his efforts rather dull. No real streets and proper buildings to peek into, just geometrically construed, abstract urban space. It took another three centuries before such city plans became the standard. And today (perhaps as a sign of our postmodern condition) the slightly lower bird’s eye view is again a strong competitor of vertical views. It is, most spectacularly, what the Eyewitness Travel Guides have relied on to build their global publishing empire.

But let’s come back to those more successful Renaissance city portraits for a minute. Have you been to Venice recently? Did you take a map and still get lost? Perhaps you should have tried the spectacular vista produced in the year 1500 by a man called Jacopo de’ Barbari [image 3].

3. Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice, 1500. Woodcut. Minneapolis Institute of Arts

3. Jacopo de’ Barbari, View of Venice, 1500. Woodcut. Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Here, then, is a dramatic expression of the desire to fly and see stuff from above (but not quite as far above as in the city plan drafted by Leonardo). Whilst Renaissance people could not really fly up into the sky, they worked out the technology to simulate flight precisely in order to portrait cities. It was a matter of, first, collecting data by climbing bell towers to look at other towers and measure angles, then walking along streets measuring distances, and finally crunching the data and construing an artificial perspective to produce a thrilling image. Oh, and of course: then you needed the money and the material to actually put your portrait on paper. In the case of the Barbari view of Venice, that meant wooden plates of an exceptional size and quality; highly skilled engravers from, possibly, Germany; sheets of paper larger than anything that was available on the market; and a printing workshop that could handle all this. The result is, at almost three metres wide, quite a lot bigger than your average map.

No wonder only a city like Venice could produce such a costly selfie, and not many copies were printed either. To see one, you can travel to Venice and visit the Museo Correr on the Piazza di San Marco – provided of course you find it – or go to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, or to the British Museum (although it is not permanently on display). The detail is stunning. As you fly across the Venetian sky, far above the highest of the Serenissima’s towers, you can zoom in here or there for close-ups. You can imagine peeking through windows to spy on the lives of the splendid citizenry of the Repubblica di Venezia. Sex, crime and conspiracy are behind every pair of curtains, around every street corner. Who wouldn’t want to be there, who wouldn’t want to see it all? If they had been given the opportunity, the Venetians would have loved drones, and they would have had drones, plenty of drones all over the place.