I’ve spent most of my career working on Henry James, the great American novelist, born in New York City in 1843, who came to Europe and ended up taking British nationality in 1915, six months before his death in 1916. He’s probably best known for the still chilling and still notoriously ambiguous horror story ‘The Turn of the Screw’ (1898), in which a highly-strung young governess sees ghosts besieging her small charges. For others his greatest and most valued work is in his first major novel, The Portrait of a Lady (1881), a classic dramatisation of the choices that await an intelligent young person facing the great, complicated world. Some are aware of his final fictional masterpiece, The Golden Bowl (1904), as a novel with such a daunting reputation for complexity that they never try it – and certainly its pleasures aren’t for everyone. James can being charmingly comic, as in the early novel The Europeans (1878), or savagely satirical as well as compassionate, as in what must still be the greatest novel about the effects of divorce on a child, What Maisie Knew (1897). James was a great novelist, but also a great writer of short stories; an interesting and persistent dramatist; a charming but often refreshingly acerbic travel writer; a great critic, especially of French, British, and American literature; a pioneer theorist of the novel; and a wonderful letter writer. He’s a very funny, extremely witty writer, and also elegiac, and tragic – and a great social observer and historian.

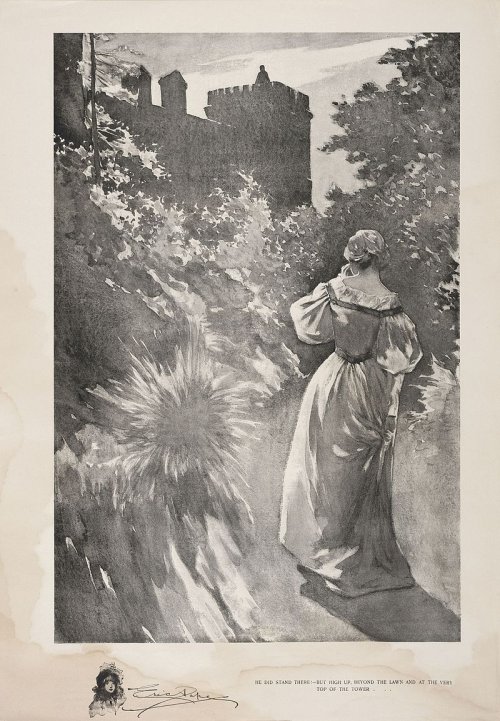

"He did stand there!—But high up, beyond the lawn and at the very top of the tower"

"He did stand there!—But high up, beyond the lawn and at the very top of the tower"

An illustration of The Turn of the Screw by Eric Pape in Collier's Weekly

So James is a world you can fall into – a very capacious and varied one: he met Dickens, Thackeray, and Washington Irving at one end of his life, and at the other end Ezra Pound and Virginia Woolf. He was constantly commenting on his time, and modernising his fictional technique; so his writing takes many forms. One is his notebooks, which I’m freshly editing.

James spent thirty years filling almost innumerable pages with his records of thoughts and story ideas, anecdotes from dinner-parties and newspapers, things noticed on his travels. He recorded, among all those that reached fruition, about 60 unwritten subjects – discussing what he called the ‘germs’, the seeds, of stories for the future. In some cases he left them there; in some he tried seriously to develop a plan for them. Some of these subjects can be boiled down to a form as pithy as a good Hollywood pitch:

Couple Asleep – Woken in Night – Husband Nervous – So Wife Goes Down – He Hears Voices – She Won’t tell Him What Happened.

Man Has been Brave By a Fluke – Lives in Terror of Having to be Brave Again.

Young Man in Mid-Western Industrial Town Fills his Room with French Culture – Refuses the Chance to Go There.

Betrayed Wife Must Have Affair to Get Revenge – Can’t.

Wife Has Long Affair – Husband Dies – They Can Marry – What’s the Problem?

I started to dwell on these – thinking first, what James himself might have done with them – and then thinking that now he simply can’t, maybe someone else could, and should. Of course these wouldn’t be the same, but the testing of James’s ideas by contemporary writers, and readers, would be the point. And James did believe in ‘variety of attempt’ in the novel, after all, in the importance of individual perspectives and sensibilities.

I had to think how to make this happen, practically. I asked my closest novelist-friends – in the first instance Tessa Hadley, and Jonathan Coe, and another friend, Susie Boyt – if they would contribute. I knew that any publisher would want some good well-recognised names already provisionally signed up to take the proposal seriously. But having no agent – few agents are very interested in academics who edit scholarly editions – I wasn’t sure how to proceed further. It happens that Susie and Tessa share an agent, the wonderful and enlightened Caroline Dawnay, who very kindly agreed to talk me through the options and the obstacles, and the best way to approach them. It was through the series of approaches and recommendations originating from her that it ended in what has seemed the perfect home for the book – Vintage, where I’ve found wonderfully sympathetic and encouraging editors. They do exist.

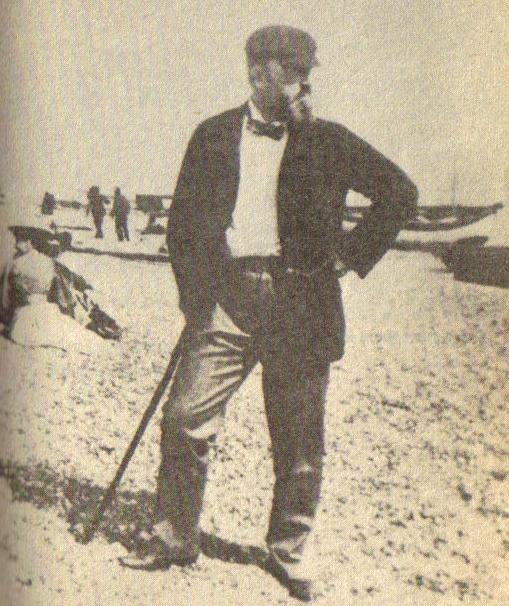

Henry James in 1897

Henry James in 1897

Scholars aren’t completely unworldly, and perhaps fortunately, I’d worked quite a lot on Henry James’ agent (who was also Conrad’s, Joyce’s, Bennett’s, Ford Madox Ford’s), James Brand Pinker. So I was interested in literary deals and negotiations as part of the context of literary history and the context in which James created. But now I was on the other side - as well as in the middle -- negotiating with my authors’ agents, some delightful and some quite hard-nosed.

This long, drawn out process was nerve-racking, but also an education in how publishing works, and fortunately the next stage was thrilling – as the stories started to come in. What has interested me most in the whole process is the creative mystery: why some writers when approached, for instance, had felt they couldn’t begin from anyone else’s ‘germ’, as if they might be infected. Some had to hunt around, sleep on it for weeks, test it out, produce drafts. And finally all combined it with something of their own, some intersection which gave it an inner necessity and edge. For instance, Amit Chaudhuri took the young man in the Mid-West and made him an ageing Anglophile Bengali stranded in Calcutta. The combination of responsibility and surprise was very pleasurable. I wanted these to be real stories, and not mock-James stories, so I told the authors they shouldn’t be pastiches (unless they were very strongly moved to that) and that the only condition was that they should be able to say that their story had been inspired by something in the James notebook entry. So these are fresh original stories, which appear unadorned in the main text. Then there’s an Appendix, with the relevant passages from James’s notebooks. So as a reader you can approach it in whatever way you please: I imagined people would like to read the stories first in their own right, then look at the appendix passage to see where it had ‘come from’; then perhaps reread it tracing how it worked. But at any rate I wanted to leave the reader free.

What was immensely heartening and moving across the range of stories as they came in was how James’s ideas had spoken to them in contemporary, twenty-first-century terms – in all cases but one : Colm Toibin’s ‘Silence’, which is in a way an intriguing companion-piece to his grand Man-Booker-winning biographical novel about James, The Master, and indeed is directly about one of James’s notebook entries. I’m deeply grateful to the fine writers who took on these ideas and made them their own, seizing the essence of James’s idea, but finding their own centre of gravity and making something so fresh and exciting from them. They stand in their own right as the authors’ own creations – but I hope that James himself would have appreciated the impulse to complete what he had started.