Imagine fairly simple tasks, like snapping your fingers, or moving your feet to the rhythm of your favourite song. Even though these are very basic actions, the truth is that your brain is engaging in endless cognitive processes: monitoring the environment and your own body, encoding signals from your senses, switching between actions, controlling your movements, and so on and so on. All processes are linked, and all brain areas are synchronising with each other.

Cognitive neuroscience tries to understand these processes, and the many difficult questions they raise about the brain and human behaviour. Nevertheless, there are also straightforward and strikingly fundamental questions that it tries to tackle, which at some point you have all probably asked yourselves. Starting with: what is the brain?

A complex series of cognitive processes allow us to perceive the beauty of paintings such as Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’

A complex series of cognitive processes allow us to perceive the beauty of paintings such as Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’

As we have seen, even simple tasks require complex cognitive processes. However, there is a common function that goes over and above all of them — that is, the conversion of different types of energies into mental representations. For instance, we constantly take in particles of light in the form of photons, and transform them into representations of colours, shapes, and visual information. We feel pressure waves in the air, and convert them into sounds, words, and sentences. By doing this we can perceive the beauty of the world when observing Botticelli’s paintings, or when listening to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. In this sense, the brain functions as a biological system that converts mere energies into meaningful cognition.

Now consider a question of the same magnitude as the first one: why do we have a brain? Surprisingly, not all species on our planet have one. You may think that the reason one has a brain is to deliberate or to elaborate intricate thoughts, but that’s not the whole story. Quoting Professor Daniel Wolpert from the University of Cambridge:

“We have a brain to produce adaptable and complex movements. Moving our body is the only way to affect the world around us. Emotions, attention, and other cognitive processes are relevant, but they are only important to either drive or suppress future movements. The golden evidence is an animal called the sea squirt: a modest animal that has a simple nervous system, swims in the ocean and at some point in its life, permanently implants on a rock. Once implanted, the first thing it does is digest its own brain and nervous system for food. So once you don’t need to move, you don’t need the luxury of a mass of neurons we call the brain.”

However, we have a brain not only for movement, but also to perceive others’ movements. Think about it: body movements are meaningless without a purpose; there can be no evolutionary advantage to move in a dynamic world if it doesn’t affect the social environment in which we develop. In this sense, body movements do not exist in a vacuum, but in interaction with others, that we constantly see, hear, touch and perceive.

We know that both body movement and perceiving others’ movements are grounded on very similar mechanisms in the brain. In the mid 90s, the mirror neurons were discovered in the brain of the macaque monkey. These mirror neurons were actively firing both when the monkey was seeing the experimenter grasping an object and when the monkey itself was doing the action. These types of neurons have also been found in the human brain, and have been linked to many cognitive processes such as imitation, social learning, action understanding and motor acquisition. The mirror neurons revealed that our own body representation in the brain, like a mental cartoon of ourselves, is engaged when performing an action, and also when seeing others performing the action. So, even in the absence of our own body movement, when seeing others move, we are covertly moving with them at a neural level.

However, all that we know about the mirror neurons applies only when we directly see others move. Paradoxically, even when the action ends, we still remember others’ bodies, actions, and how to move ourselves. So, how do we hold this body information in mind?

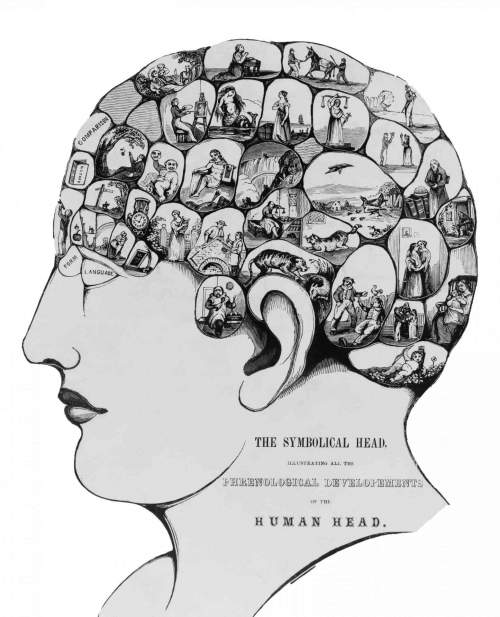

The brain holds memories of movement and artistic perception, as seen in this symbolical drawing

The brain holds memories of movement and artistic perception, as seen in this symbolical drawing

To reveal this, we ran a series of experiments asking our participants to remember different movements while we recorded their brain activity using a technique called electroencephalography. Every time our participants held a body movement in memory, the neurons in parts of the brain started to fire, revealing structures of the brain that are engaged in remembering these body movements. Results showed that while holding body information in memory, we also engage our own body representation in the brain. Depending on the quantity of body information to be held in memory, our brains engage in more and more activity over time. This means that even if the original body movement we perceived disappears from our visual field, or when we learn a new action or motor task, we can bring these movements back to our inner world by activating those memories based on our own body represented in the brain.

Looking forward, many exciting questions remain in the understanding of the body-brain relationship in cognitive processes. Firstly, in neuroaesthetics: how do we perceive and feel art depicting bodily matters in the brain? Secondly, how will we interact cognitively with humanoid robots that look like us, and what impact will this have on us? Lastly, there is the question of consciousness and the body as the container of it.

To answer these groundbreaking questions, we are required to understand that any cognitive process and ultimately, the human brain, can only be truly understood when considering the whole picture, and this includes the body. So, just keep in mind that we do not truly see and remember others by using our eyes in the brain, but by engaging ourselves in the form of our own body represented within it.