For any theoretical physicist, there is a moment when you know you have “made it”, and that moment is when you receive your first letter from someone who claims to have a new theory of physics.

When Stephen Hawking receives these letters, he probably just chucks them into a big pile marked “nutters”, and gets on with his research. But for junior researchers, the honour of having someone write to you makes such correspondence worthy of serious consideration.

I received my inaugural letter shortly after publishing my first article in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity. My correspondent, who we will call ‘Richard’, began:

The attached paper argues that until we do Galileo’s experiment, we cannot be certain whether or not an important stone in gravitational physics has been left unturned.

Galileo’s experiment, to which Richard refers, is a classic question given to undergraduate physicists which is approximately this: imagine that you dig a hole right through the centre of the Earth (ignoring the obvious practical difficulties of this feat), and you jump into it. What will happen?

Richard continues as follows:

Fundamental physics and cosmology are heavily invested in various extreme cases and conditions of energy, density and velocity. Why not slow down, lighten up, and look where we have not yet looked? Why merely pretend to know what happens in this case?

These questions are somewhat rhetorical, but in fact these are some of the deepest and most fundamental questions in physics. Why are we so bothered with black holes, and high energy particle collisions? And why do we not test every individual possibility, simply assuming we know what the answers will be?

The answer to the ‘hole in the earth’ problem is logical but also rather surprising if you have never given it much thought. You will fall at first as you would at the surface of the Earth, accelerating at around 1 g (or 10 meters per second squared). But as you approach the centre of the Earth, the force of gravity decreases to zero, meaning, according to Newton, that you have zero acceleration at this point. So, if you could somehow stop at the very centre of the earth, you would just bob about there, weightless. But since you just jumped down a hole from the surface of the Earth, you won’t be stationary when you reach the centre; you’ll be going very fast indeed. This means that you will shoot through it and continue up to the other side. At this point the force of gravity increases again, but in the opposite direction, pulling you back towards the centre of the Earth. You slow down until you come to a stop at the opposite side of the Earth, and then you begin to fall again. The result is that, like a child on a swing, you will oscillate back and forth between the two surfaces of the Earth, in what physicists call simple harmonic motion. It sounds rather fun.

But the parts of the letter that really interested me were the two key questions: why do physicists think they know what will happen in situations which are untested? And why are we so obsessed with high energies?

Let’s take a look at the first question. Why do we think that we know what will happen if we drill a hole in the Earth and drop someone down it? The reason is that physicists believe that the laws of physics are “spatially invariant”, that is, the same everywhere in space.

When we say the laws of physics, we mean fundamental laws like how gravity behaves, or how the forces between atoms are governed. We don’t expect, for example, that if we go to another planet, then gravity will make things fall “up”. This seems obvious, and there is an enormous body of observational evidence to support it, but it is actually just an assumption that underlies theoretical physics — it can never be truly proved unless we travel to every part of the universe and check.

But that is effectively what Richard is proposing that we do. His theory is that part of the universe (the bit inside the Earth) behaves differently to that outside. But it is incredibly difficult to build a physical model which is consistent with all the observations we have, but that also predicts spatially-changing laws — several physicists have tried, and failed. But if we accept that the laws have to be the same everywhere, then we can, in theory, predict what will happen anywhere, without having to test every scenario.

The same is true of time — we don’t expect that on a Tuesday the laws of physics will be different to on a Monday. In fact, most physicists think that physical laws are time-invariant.

But what about energy? Energy is more interesting, because, unlike with space and time, fundamental laws do change with different energies.

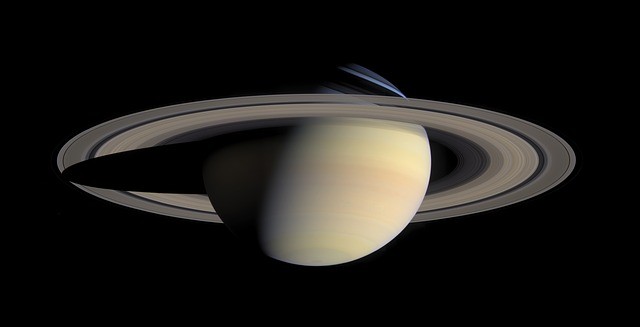

Let me give you an example. Imagine for a moment that you are an alien, living on Titan, one of the moons of Saturn. Titan is cold — it has a temperature of around -180°C . Here, water is always in solid form; in fact, ice is hard as rock. It might be difficult for you to imagine that if you could heat it up, it could become a liquid. But if you managed to get a fire going somehow, you would find that at zero degrees celsius water undergoes a sudden and seemingly mysterious transition. Its properties, like density and its ability to flow, change dramatically with only a one degree rise. But it’s not that the laws of physics which govern the bonds between water molecules are changing when you heat up water; they remain exactly the same. Rather, it is that new effects come into play at higher energies which were suppressed at lower ones, like vibrational interactions. But without actually heating up the water, you would almost certainly not have known that this transition would occur, because there was no sign of a change until it happened. By going to a higher energy, you probe deeper into the nature of water molecules, and understand better the laws of physics that govern them.

On Titan, one of Saturn’s 53 moons, water is always in solid form

On Titan, one of Saturn’s 53 moons, water is always in solid form

But that’s not entirely accurate. Fundamental laws are just that, fundamental, and so they must cover all energies. The point is that we expect the laws to have some strong dependence on energy, such that we will see different phenomena at different temperatures. And, crucially, we can’t know about how the laws will change at higher energies just by testing them at lower ones. Unlike with space, we actually have to go there and test them to know what they are.

This is exactly what happens at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider — particles are smashed together at higher energies because we think that we might see things that we don’t see at everyday temperatures. Sometimes physicists sound a bit like crazy people, suggesting magical effects that happen in some higher energy realm. But this is simply a reflection of the fact that we have evolved at “everyday planet Earth” temperatures, and that our “instincts” are therefore based on what we expect to see in those conditions.

This is the beauty of physics: we learn to question our instincts, and to understand that what sounds like magic is just the hidden reality of the universe. But it doesn’t mean we can just abandon our sense of reason, and propose any theory we like. Our theories must agree to what we observe around us every day, and that puts extremely strong constraints on the range of possible ideas that can be explored. So, whilst I’m grateful to anyone that makes me question the nature of the universe, I’ll leave the digging to Richard.