Humans have increased the amount of CO2 in our atmosphere; that is clear. This CO2 is the main cause of global warming, but what is less widely acknowledged are the many ways that CO2 affects our planet. Imperial College physicist Heather Graven tells us about them.

In 2016, the atmospheric carbon dioxide or CO2 concentration was 404 parts per million, approximately 40% higher than it was before the start of the Industrial Revolution around 1870. Atmospheric CO2 concentration is now higher and increasing faster than at any time in at least the last several million years. This is because human activities are adding CO2 to the atmosphere through three main processes: fossil fuel combustion, the conversion of forests to agricultural lands, and cement production. This additional “anthropogenic” CO2 is the primary cause of climate change, a phenomenon which causes temperatures to increase, precipitation patterns to change, and ice covering both our land and oceans to shrink.

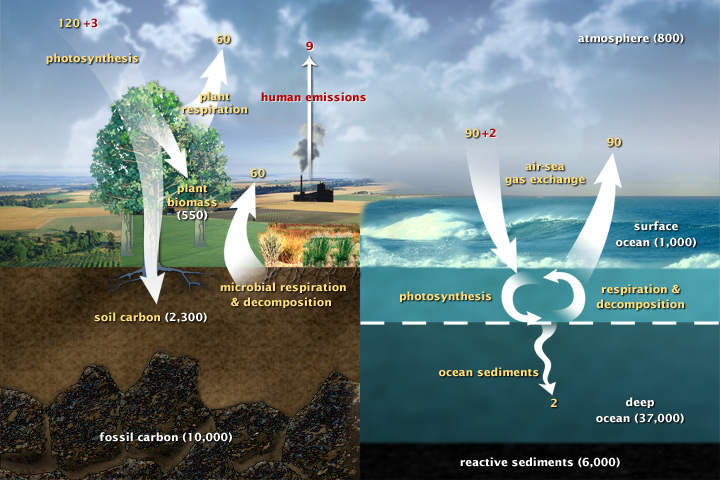

Atmospheric CO2 concentration would be even higher now, and climate change even more severe, were it not for the exchanges of carbon between the atmosphere, the ocean, and the plants and soils on land. This interconnected web of processes and interactions is called the “carbon cycle”. About half of the CO2 released by human activities has been absorbed by the ocean and by the plants and soils on land, giving us a “50% discount” on climate change. While the carbon cycle has reduced climate change by removing some CO2 from the atmosphere, it is also sensitive to changes in climate. Changes in climate can affect how efficiently anthropogenic CO2 can be removed from the atmosphere.

For example, plants on land can increase photosynthesis as a result of higher CO2 concentration and warmer temperatures. At the same time, warming temperatures increase the respiration of dead leaves, roots and other organic materials in soils by microbes, releasing more CO2 back to the air. Areas of frozen, carbon-rich soils known as permafrost are now thawing as a result of climate change. After being frozen for thousands of years, the organic material in permafrost soils is now subject to respiration by microbes, and a significant fraction of permafrost carbon could be released as methane (CH4), a stronger greenhouse gas than CO2. On the other hand, warmer temperatures can also cause heat stress in plants and contribute to drought, thereby reducing photosynthesis. Drought and heat stress can sometimes lead to tree death, which has long-term impacts on ecosystems and the carbon cycle.

Another example can be found in the ocean, which is accumulating carbon as some of the CO2 in the atmosphere dissolves in the water at the ocean surface. The uptake of CO2 by the ocean reduces the atmospheric CO2 concentration, but it causes ocean acidification because the dissolved CO2 reacts with water and decreases ocean pH. As ocean water warms and becomes more acidic, the efficiency of CO2 uptake by the ocean is reduced over time. Furthermore, as the upper ocean warms and receives freshwater from melting ice and continental runoff, surface water becomes less dense and more buoyant. These changes are causing sea levels to rise, while at the same time making the ocean more stable so that dissolved CO2 from the surface is less easily mixed into the deep ocean.

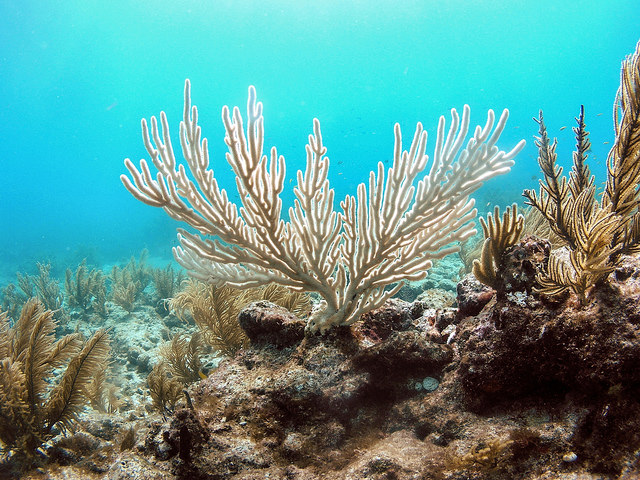

Marine ecosystems are also sensitive to temperature and ocean water acidity. Higher temperatures can enhance photosynthesis by phytoplankton, tiny free-floating algae. However, just like their terrestrial counterparts, other marine organisms experience heat stress, such as during coral bleaching events when corals eject the colourful algae that live on them, revealing the white carbonate shells of the corals and starving them of their food source. Disruptions to the ocean carbon cycle could have severe impacts on marine fisheries via a cascade of effects through the food chain.

To predict the effects of climate change on the global carbon cycle, and vice versa, we use numerical models. Many different physical and biological processes must be represented within the computational limits of the models so these processes are often simplified. The simplified version of a process in a model is called a parameterisation. One example of a process that is parameterised is the exchange of CO2 across the ocean surface. Not all of the processes involved can be explicitly included within a global model, so a parameterisation is used that relates CO2 exchange to wind speed. As computational capabilities grow, higher resolution models that include more processes and complexity continue to be developed.

Research groups across the world regularly coordinate their model simulations of historical changes and future scenarios in order to compare different models. Comparisons of different models show that the carbon cycle and the natural CO2 removals are a major contributor to the overall uncertainty in future climate change. Improving their representation in models is a top priority for climate modelling.

Carbon cycle research is particularly important for countries constructing policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In December 2015, more than 190 countries agreed to cooperate to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions in the Paris Agreement. The main goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to no more than 2 °C. Understanding the carbon cycle is critically important to achieving this goal, because the carbon cycle determines how much of the CO2 that is emitted will remain in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming. Therefore, carbon cycle scientists are needed to estimate how much CO2 can be emitted while maintaining a good chance of keeping warming below 2°C, and to evaluate progress on the Paris Agreement goals over the coming decades.

In order to provide policymakers with the best possible information, scientists must continue to investigate the vast network of interconnected biological, chemical, and physical processes that govern global climate. A major focus has to be the interactions between climate and the carbon cycle. Continued measurement of atmospheric CO2 concentration and other aspects of the global carbon cycle will be essential for understanding and monitoring changes to our environment.

Something similar:

by Lidunka Vocadlo

Standing on the Earth, you’d probably think it’s made of rock. And you’d be right – mostly. In fact, what you’re standing on is the Earth’s crust.

The crust is broken into plates which fit together like a jigsaw, ...

Something different:

by Matthew Dyson

What do all the electronic gadgets you own have in common? Aside from using electricity, they are always solid, box-like objects, regardless of whether they are mobile phones, computers, TVs or solar panels. This rigidity, which is imposed by the ...