May 1958, Algeria.

Large crowds gathered on the main squares of Algiers and Constantine, chanting “Long live French Algeria” and “Long live de Gaulle”. While the wives of French Military officers and settlers helped Algerian women remove their veils, selected Algerian women read from a script that conceptualized the Muslim veil as a “barrier between two communities”.

The text read:

We are aware of how far our traditional dress, our reclusive existence, are factors that separate us from our French sisters of a different religion to ours. We wish to engage fully in the route to modernity and to profit from the exciting epoch which Algeria is currently traversing to accelerate our progress.

These spectacles were organized as part of French-led “emancipation” campaigns devised by the colonial power in Algeria. The previous year, in July 1957, the main radio station in Algiers urged women to remove their veils. General Jacques Massu, a key figure in the French military who led the suppression of the Battle of Algiers that same year, demanded the banning of the veil altogether. “The order for unveiling”, he wrote, “should be given now firmly and unambiguously”. At the same time, numerous women’s associations proliferated in Algeria, aimed at persuading Algerian women to “liberate” themselves from the veil, considered by the French to originate from an oppressive tradition. These ideologies — targeted specifically at women — became a key aspect of colonial propaganda and of so-called “military feminism”.

These mass unveiling ceremonies took place in the midst of armed conflict. This was the year that the Algerian War of Independence — one of the most violent decolonial conflicts in the twentieth century — entered its fourth year. It would result in Algeria gaining independence from France in 1962. Staged at a moment of political turmoil in mainland France, which was struggling politically and financially to maintain its colony in North Africa, these spectacles were organized in order to demonstrate that Muslim women had been won over to European values and away from the independence struggle. For this purpose, these unveilings were presented as entirely spontaneous acts initiated by the Algerian women themselves. Yet under the pretence of women’s emancipation lay a long-standing strategy of psychological warfare that was devised to end the revolution before Algeria could claim political independence.

Orchestrated by the military, the unveilings were meant to be organised and received with “applause and expressions of sympathy”. Yet women did not participate voluntarily in these ceremonies. Many of them were transported from nearby villages to larger cities by army trucks. In Constantine, a city in northeast Algeria, the script was read by Monique Améziane, who unveiled before a crowd, surrounded by key military figures. It was discovered years later that she had never even worn the veil prior to the ceremony. She was forced to participate because her step brother was detained by the French army, tortured, and threatened with execution. Monique was told her public appearance and unveiling would save his life.

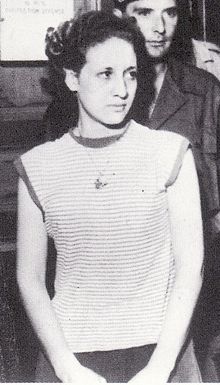

Resistance fighter Zohra Drif

Resistance fighter Zohra Drif

These colonial unveilings were presented as aiding the emancipation of Algerian women. However, organisations which brought women together had already existed across the Arab world since the late nineteenth century. Moreover, women were becoming increasingly politically active within the Algerian Independence movement. Sixteen percent of the resistance movement was made up of women, though many more aided its efforts by hiding members and providing food. Today, some of these female resistance fighters, Zohra Drif being one of them, sit in the Algerian Parliament. The histories of women’s liberation and feminism in Algeria are thus closely related to the war of independence.

Under colonial rule, the veil became a symbol for those who did not subscribe to the European system of thought. As a visible, public marker of cultural and religious identity, it hindered the image of French Algeria as a colony that fully absorbed the values of the colonising power. The veil visualised the differences between Algerians and French settlers, and as such, in the eyes of the French military, it needed to end. This was particularly important as the outside world was beginning to watch the conflict with increasing concern. Removing veils would serve to create the image of Algeria as united with eurocentric ideals.

In this way, the Algerian War of Independence launched the politicisation of the female body and women’s sartorial choices. In 1959, the Martinique-born psychiatrist and anti-colonial writer Frantz Fanon, a member of the National Liberation Front in Algeria, described the philosophy behind the French doctrine in Algeria as follows:

If we want to destroy the structure of Algerian society, its capacity for resistance, we must first of all conquer the women; we must go and find them behind the veil where they hide themselves and in the houses where the men keep them out of sight.

Fanon understood that a colonial power could not conquer Algeria without winning over the women to European so-called “norms”. Pointing to a highly gendered and sexualised colonial relationship, Fanon argued that:

Every rejected veil disclosed to the eyes of the colonialists horizons until then forbidden, and revealed to them, piece by piece, the flesh of Algeria laid bare.

Fanon drew a clear parallel between unveiling and physical violence, stating that

…the rape of the Algerian woman in the dream of the European is always preceded by a rending of the veil. We here witness a double deflowering.

As the colonial power sought to unveil Algerian women, the Algerian nationalists conceptualized the veil as a symbolic locus of tradition, culture and resistance. The veil – alongside the female body – became an outright battleground, torn between colonial violence and nationalist struggle.

The traditional white Algerian veil — the haïk — continues to carry connotations of independence and resistance against European colonialism today. In 2015, a group of women protested in Algeria asking for the return of the haïk, rejecting at the same time the dark-coloured, black veils that are increasingly being imported from the Middle East. They consider the burqa and the niqab to be as foreign to Algeria as the haïk is native to it.

The Algerian War of Independence saw the Muslim veil move into the midst of a violent conflict. Though it was during this war that the veil became conceptualised as a garment fundamentally at odds with a French — and wider European — identity, the contested status of the Muslim veil continues to fuel current debates on the continent.

Today, France’s Muslim community forms around 8% of its population and is the largest Muslim minority in Europe. Despite this, the Muslim veil remains a contested choice of clothing. In the summer of 2016, a woman walking with her children on a beach in the French city of Cannes was fined for wearing leggings, a tunic and a headscarf. The official reason she was given for being fined was that her clothes failed to “respect good morals and secularism”. She was asked to wear her headscarf as a bandana or leave the beach. When the wearing of the hijab — a veil which covers the head and neck — was outlawed in French schools in 2004, it was claimed that it formed a manifestation of political Islam and thus contradicted the country’s secular ideals. The recent proliferation of bans surrounding certain elements of Muslim clothing, most notably the full-face veil in Europe and beyond, illustrate how Muslim women’s sartorial choices have once again become sites onto which fears and ideologies are projected.

When a ban on full-face veils was introduced in Austria in January 2017, it was estimated that only 150 women in the whole country wore the burqa or the niqab, forming 0.002% of the whole population. Yet little effort was made to begin a dialogue with these women, leaving their personal choices unacknowledged.

In recent years, Muslim women have marched during protests in France veiled in the colours of the French flag: a response to France’s long history of struggling to allow Muslim identities to sit comfortably alongside other notions of French national identity. In French Algeria, only Algerians who denounced Islam were granted French citizenship, despite the fact that Algeria formed an integral part of the French Republic from 1848 until independence in 1962.

In Europe, the veil has been time and again portrayed as foreign to the continent’s mentality. By distancing the garment from its wearer’s subjectivity, it has become a screen onto which we project various ideologies. As a result, women’s agency has largely been downplayed. Yet it is precisely the various approaches Muslim women take towards veiling that disrupts the construction of the veil as — to use the French colonial terminology — a “barrier” between communities. The agency of women fatally complicates this divisive, and constructed, narrative.