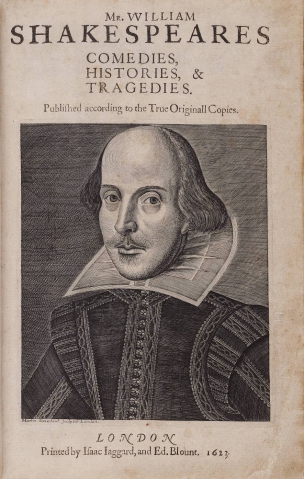

Martin Droeshout, William Shakespeare (1564-1616). Engraving. British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0]

Is William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon the real author of the Shakespearean plays? The so-called anti-Stratfordians think not. The Shakespeare scholar René Weis disagrees and presents three pieces of evidence against conspiracy theories.

narrated by Angus Waite and Vidish Athavale

music by Chris Zabriskie, John Dowland (performed by David Hernández Romero) and Sergey Chereminisov

The very idea of a global, watertight conspiracy over mere plays, right across Elizabethan and Jacobean England, verges on the almost self-evidently absurd. Yet that is what some would have us believe regarding the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. Not only are we expected to believe that all those in the know about the real author of the plays kept their secret, but we would also inevitably be impugning the integrity of those who eloquently bore witness to Shakespeare’s authorship. Not to mention the fact that by doing so we would be robbing Shakespeare of his extraordinary achievement, posthumously strip the greatest writer of all time of his fame in the name of what is ultimately ignorant snobbery: a glover’s son with a mere grammar school education up to the age of 15 could surely not, the argument goes, have written these masterpieces, steeped as they are in some 24,000 words of English, a peerless command of rhetoric, extensive knowledge of classical authors, and the confidence to write about Kings and Queens and English history.

Why do many otherwise perfectly rational people want to doubt that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare, preferring instead to believe that they were written by someone who died in May 1593 (Christopher Marlowe), or in 1604 (Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford)? Marlowe was killed before any of the major Shakespeare plays had appeared and the Earl of Oxford died before King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, and all of the romances, including The Tempest. But, we are told, perhaps Marlowe did not die at all in 1593 but instead went underground to continue writing under the name of Shakespeare. Quite apart from the fact that Marlowe and Shakespeare deployed radically different styles (compare, for example, Tamburlaine and The Jew of Malta to their Shakespearian equivalents, Richard III and The Merchant of Venice), in the early 1920s Leslie Hotson discovered the coroner’s inquest concerning Marlowe’s death during a tavern brawl in Deptford.

It was not just in 1590s London that people assumed that Shakespeare had written the plays, but also in the hallowed halls of Cambridge. When around 1600 the students at St John’s College staged a series of plays called Parnassus, three anonymous closet dramas, they alluded repeatedly to Romeo and Juliet while quoting Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. The wits and amateur thespians of the Parnassus plays elsewhere demonstrate their keen knowledge of who was who in Elizabethan drama. They know all about former Cambridge student Marlowe who, they claim, was ‘happy in his buskind muse, / Alas unhappy in his life and end, / Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell, / Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell’. Marlowe’s mercurial literary gifts, his violent death, his outrageous political views and atheism, and also his homosexuality are here alluded to. Cambridge students at the time obviously distinguished between Shakespeare and Marlowe as did of course many others commentators in the period.

All the players of the company that staged the plays, first as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and later as the King’s Men, are implicitly accused of dishonesty by the so-called anti-Stratfordians, for colluding with the fiction that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon had written the plays in order to protect the identity of the real author, a hidden genius whose identity can only be guessed at. So is a dramatist who ranks first and foremost among those who bear witness to Shakespeare’s authorship, his younger friend Ben Jonson, the most voluble of men, a brilliant playwright with a ferocious critical intelligence. In his ‘diary’ (which is really a commonplace book) Jonson remembers that

the players have often mentioned it as an honour to Shakespeare that in his writing, whatsoever he penned, he never blotted out a line. My answer hath been ‘Would he had blotted a thousand’, which they thought a malevolent speech. I had not told posterity this but for their ignorance who chose that circumstance to commend their friend by wherein he most faulted; and to justify mine own candour, for I loved the man and do honour his memory on this side idolatry as much as any. He was, indeed, honest and of an open and free nature, had an excellent phantasy, brave notions, and gentle expressions, wherein he flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped.

Here is Jonson talking about Shakespeare’s facility while daring to take issue with it. Even Shakespeare, Jonson notes, could have done with more discipline and rewritings (or ‘blottings’), a barb that may arise from Jonson’s neo-classical preferences as in his own play, The Alchemist, perhaps the most tightly knit comedy in the English language. Shakespeare wrote too much too quickly, Jonson implies. In case his stricture should be construed as professional jealousy — Shakespeare was vastly more successful than Jonson — Jonson reassures that it is not: on the contrary, he adored Shakespeare the man for his generous nature and admired his imagination, only wishing that it had not overflown so.

The point is that Jonson, an inveterate gossip, knew Shakespeare very well. Not only does he recall his dead friend in his diary, but in the prefatory material to the 1623 Folio [see image], a monumental work of 36 plays by Shakespeare, published by fellow members of the King’s Men, John Heminges and Henry Condell, he authenticates the Martin Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare. In a short poem, ‘To the Reader’, Jonson tells us that ‘This figure that thou here seest put, / It was for gentle Shakespeare cut.’ The engraving is a fair likeness, Jonson states; after all he was there and was in a position to tell.

We are not, which is why the Droeshout engraving has enjoyed a poor press with posterity, as a somewhat crude piece of work and one which seems to fail to express true genius, assuming that there is such a thing. But whatever its merits or shortcomings, the Droeshout is vouched for by Jonson and was accepted as genuine by the editors of the 1623 Folio who knew Shakespeare well. Moreover, Jonson added a prefatory elegy to the 1623 Folio, ‘To the memory of my beloved the author Mr William Shakespeare and what he hath left us’, which remains the greatest tribute ever to Shakespeare, and by none other than his most acclaimed rival in the theatre.

Finally, in one of his plays Shakespeare himself refers, irrefutably, to someone else from Stratford-upon-Avon, the publisher and printer of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, Richard Field, Shakespeare’s senior by two and a half years. The two boys grew up within a hundred yards of each other and would have attended the same school in Stratford. The reference to Field occurs in the late play Cymbeline, when the Roman commander comes across a young woman disguised as a young man:

LUCIUS Thou mov’st no less with thy complaining than

Thy master in bleeding. Say his name, good friend.

IMOGEN Richard du Champ [Aside] If I do lie and do

No harm by it, though the gods hear, I hope

They’ll pardon it.

In her male disguise Imogen assumes the name of ‘Fidele’, which means ‘the loyal one’ (French fidèle). Fidele is a virtual anagram of ‘Field’ while Imogen’s ‘Richard du Champ’ is French for Richard Field. The commonly accepted date for Cymbeline is 1609. That same year Shakespeare’s Sonnets were published. If in the play he alludes to one of his real life friends, in the poems he tells us that it is really himself. The two most striking sonnets in this respect are 135 and 136. In the former, he plays repeatedly on his name while talking to his lover: ‘So thou, being rich in Will, add to thy Will / One will of mine, to make thy large Will more’. In the latter (136), he bluntly declares: ‘Make but my name thy love, and love that still; / And then thou lov’st me, for my name is Will.’

And not, one might add, Kit (Marlowe) or Ned (Earl of Oxford), or any other of the scores of names that have been put forward instead of Will Shakespeare.

Something similar:

by Emma Pauncefort

Taking a ‘year out’ upon leaving school has become pretty commonplace for the English private school girl or boy. Even more commonplace is the decision to spend the year away from books, and venture on a so-called ‘gap year’. Fresh-faced ...

Something different:

by Jason Dittmer

This is a story about an all-American winner; a man loved by millions; a man who, as President, could single-handedly solve the problems facing the USA. That man is Captain America.

Cast your mind back to 1980 and the 250th ...