Right now inside your body, trillions of cells are performing their defined functions. Bone cells are providing support to the body by maintaining a very sturdy consistence, muscle cells are contracting, and blood cells are carrying oxygen and protecting the body from infection. In most cases, cells like these follow a path of gradually becoming more specialised. For instance, first they become blood cells, then white blood cells, then a particular type of white blood cell, and so on. In this process they cease from being capable of becoming, for example, bone or muscle. In other words, they restrict their differentiation potential.

A stem cell is capable of two defining features: producing an exact copy of itself (which is a form of self-renewal), and embarking on the journey of becoming a specialised cell (which is called differentiation). The very first cells, having derived from the fertilised egg, are stem cells by definition, and they are said to be “totipotent” as they can give rise to all tissues, as well as the placenta. A subset of cells then forms, consisting of what we call “pluripotent” cells. These can give rise to virtually every type of cell within the adult body. Later on in life, most tissues maintain a subset of cells referred to as “tissue stem cells”. These cells maintain the tissue by allowing, for example, the innermost layers of your skin to produce new cell types while the upper layers peel off.

For a very long time this was thought of as a one way street, from the fertilised egg through to the developed adult, from totipotent cells to pluripotent cells to tissue stem cells. However, ten years ago, research in Shinya Yamanaka’s group demonstrated the possibility of inducing pluripotency, in which cells taken from the skin of adults could be reversed to an embryonic-like stage. This research led Yamanaka to win the Nobel Prize in 2012.

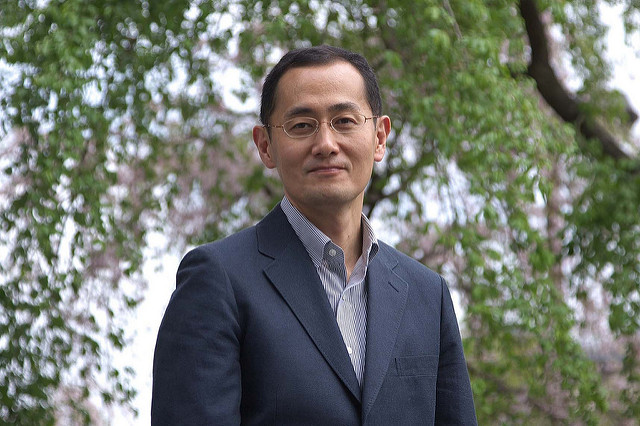

Shinya Yamanaka and his colleague John Gurdon were awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering that mature cells could be reprogrammed to become pluripotent. By Rubenstein [CC BY 2.0]

Shinya Yamanaka and his colleague John Gurdon were awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering that mature cells could be reprogrammed to become pluripotent. By Rubenstein [CC BY 2.0]

This technology is now relatively mature, although the intricacy of the phenomenon is far from being fully understood in terms of its biological mechanisms. It offers a valid and ethically appealing alternative to the derivation of embryonic stem cells from human embryos. Cells derived from a particular individual can be reprogrammed to induce pluripotent stem cells, expanded virtually and indefinitely, and then differentiated to selected cell types. One can imagine the possibility of replacing cells to combat diseases where particular cell types are lost, such as in Parkinson’s and diabetes. This process, known as cell therapy, comes in two flavours, autologous (where cells are derived from the same patient who becomes the recipient) and allogeneic (where cells are expanded from one particular individual and provided to different patients). Both strategies come with important hurdles to jump over. If we were to simplify, the first option keeps the doctor happy, as immune reactions should not happen in response to foreign cells entering the body, and the second keeps the pharmacist happy, as the cells can be expanded massively and can become an actual therapeutic product. Despite the fact that the model exists, there are many obstacles to be overcome. The path is still long, with costs being significant and in many cases prohibitive at the moment.

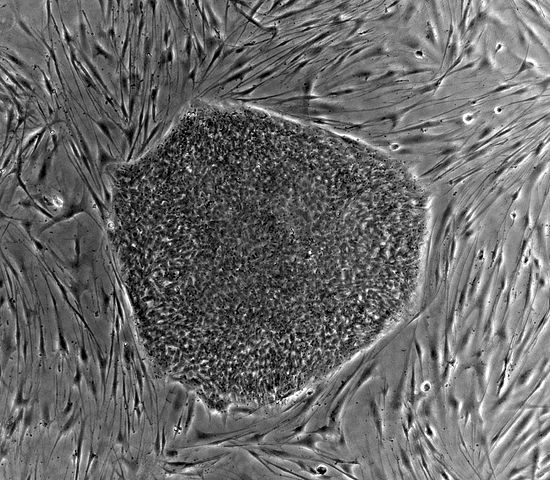

Before Yamanaka and Gurdon’s discovery, it was thought that pluripotent cells could only be derived from embryonic stem cells, like the ones pictured here

Before Yamanaka and Gurdon’s discovery, it was thought that pluripotent cells could only be derived from embryonic stem cells, like the ones pictured here

However, it is possible to use stem cells derived from selected individuals to study how a particular disease develops using cells cultured in the laboratory, such as in disease modelling, or to find targets and chemicals that can be further developed as therapeutics. This path is complementary to the cell therapy path, and offers the advantage of less stringent conditions to maintain cells in the laboratory, as cells are not intended to be put into people at the end of the process, and therefore can be exposed to more variable culture conditions. Microscopy, liquid handling, and computational power have all come very far in the last few decades, allowing the possibility to test a huge number of conditions on cells, while observing their reactions in great detail at a cellular level.

This is defined as high content analysis. In the past, the emphasis has been on high throughput analysis, where a vast number of conditions are investigated. This is done by, for example, screening a million different chemicals to be developed as a drug, but the actual amount of information derived from each experiment, such as the efficacy of an enzymatic reaction, is low. In order to understand what high throughput analysis is, you can imagine an airport where a dog sniffs a large number of bags and barks when a particular substance reaches a level its nose can detect. On the other hand, during high content analysis, the X-ray machine provides a lot of information for each bag through detailed images, but can’t look at as many bags as the dog is able to. These two fields have developed in parallel and, by combining both processes, it is now possible to obtain a huge amount of information from images of cells while assessing many different conditions in the process.

HipSci, which stands for Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Initiative, is a Cell Phenotyping programme at the centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine at King’s College London and it aims to characterise and further understand induced pluripotent stem cells from healthy individuals and selected diseases by combining information from their DNA, RNA, proteins, and the way the cells react to external conditions. All of this will be done by analysing images. This is a foundational exercise to understand what portion of cell behaviour can be related to their genetic information.

Based on the experience gained through this collaborative phenotyping project, a ‘stem cell hotel’ is being built. This is a structure that allows scientists to use the devices and expertise of the centre to bring in cells for a limited period of time and answer specific biological questions via the analysis of images. This will be done by observing how the cells respond to certain changes in environmental conditions. The dialogue within the industry in this respect is of great importance; working with technology developers is beneficial for both sides. There is a lot to gain from a university environment actively engaging in scientific dialogue with industry. The ‘stem cell hotel’ model can help us bring scientists from both worlds together, translating academic research into everyone’s well-being.