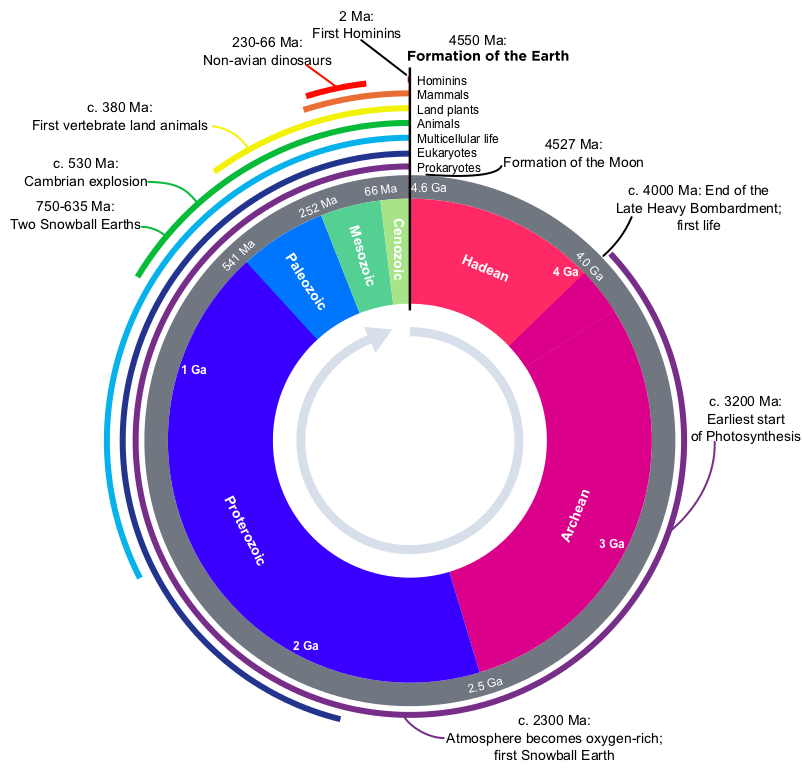

When we consider ancient life on Earth, our minds conjure images of plains populated by land animals, like gentle-giant dinosaurs. However, land animals are a relatively recent phenomenon. The Earth is 4.56 billion years old, while animal life on land has only existed for the past 500 million years. Dinosaurs are even more recent inhabitants, coming onto the stage between 230 and 65 million years ago.

The numbers involved are too vast for us to comprehend, but we can think of them as the time on a 12-hour clock. Let’s imagine the Earth is formed at 12 o’clock noon, and today’s date, 4.56 billion years later, is 12 midnight. Land animals would appear as the hour hand passes 10 o’clock, with dinosaurs tromping over the Earth between 11:00 and 11:30. However, life in the Earth’s oceans has existed for considerably longer: since around 4,000 million years ago, or at around 2 o’clock on the clockface. This means that the Earth has been inhabited by life for almost 90% of its existence, with land animals existing for 10%, and we humans for less than 0.04%.

Geological clock representing major events in Earth history

Geological clock representing major events in Earth history

So why did life appear at 2 o’clock, and not earlier? Life requires some specific conditions to survive, especially in terms of temperature. For one, water needs to be liquid for life to come into existence and thrive, and that means that a habitable planet needs to have average temperatures between 0 and 100°C.

Comparing the Earth to our planetary neighbours, Venus and Mars, shows just how unique our planet is in this respect: Venus has an average surface temperature of around 450°C, and Mars of around -50°C. Therefore, a big question is why the Earth is unique in having maintained a temperature suitable for life for most of its existence.

The existence and endurance of life on Earth becomes even more remarkable when we consider all the dramatic changes that the Earth has undergone over the millennia: the formation and breakup of huge supercontinents, massive volcanic eruptions, meteorite impacts, and the increase of atmospheric oxygen content from virtually nothing to an atmosphere that is breathable for us today. Even more striking is the remarkable stability of our climate – average ocean temperatures have only varied by around 25°C for the past 3.5 billion years, which has made animal and plant life possible.

So what makes the Earth so uniquely suitable for life? Unlike Venus or Mars, the Earth has an active plate tectonic system, which continuously produces and destroys the crust. The same system also gives us active water, oxygen and carbon dioxide cycles, as material is subducted down into the Earth’s interior, and eventually re-erupted from volcanoes. However, while tectonics give the Earth active water and gas cycles, the tectonic system itself moves too slowly to be the process that actively maintains the climate.

Some theories, such as the Gaia Theory, suggest that life itself has been modifying the climate, so as to keep the Earth habitable. While it is indisputable that life has shaped the planet – for example, by oxygen formation through photosynthesis – it is much less clear if life can actively moderate the climate to keep a continuously habitable planet. In addition, for about the first billion years of life’s existence on Earth, life was probably not a significant enough force to be able to mitigate climate variations.

To understand the Earth’s remarkably stable long-term climate, we must focus on the carbon cycle – specifically what is known as the long-term carbon cycle, which operates on timescales of more than tens of thousands of years. In this process, carbon dioxide from volcanic activity is added to the atmosphere, and subsequently removed from the atmosphere by two processes: first, the physical burial of organic carbon in coal, oil, gas and shale, and second, the chemical formation of carbonates, such as limestone or coral reefs, in the oceans. Carbonates contain carbon, and so their formation locks it up for long time periods.

Carbon dioxide is the main greenhouse gas with a long time-period effect. Therefore, to maintain a long-term stable climate, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere must be controlled. However, the input through volcanism is random, meaning that the removal processes of CO2 must be the controlling factor in climate stability.

Both organic carbon burial and carbonate formation are processes controlled by the weathering of rocks on the continental landmasses. As rocks are dissolved through contact with rain and rivers, the components of which they are formed are transported to the oceans. This provides nutrients for marine life to produce and bury organic carbon, and also provides the chemical constituents to form carbonates in the oceans. Therefore, it is the processes that control chemical weathering on land that ultimately control long-term climate.

But it’s not enough to just have an ongoing CO2 removal mechanism for the climate to remain stable. This mechanism must also be able to respond to the changing amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. If there is a massive volcanic eruption, this will increase the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and cause changes in climate. In the past this has occurred when enough lava was erupted to cover the continental USA several kilometres deep. If the CO2 removal mechanism had not responded to counteract these huge CO2increase, the Earth’s climate would have spiralled out of control.

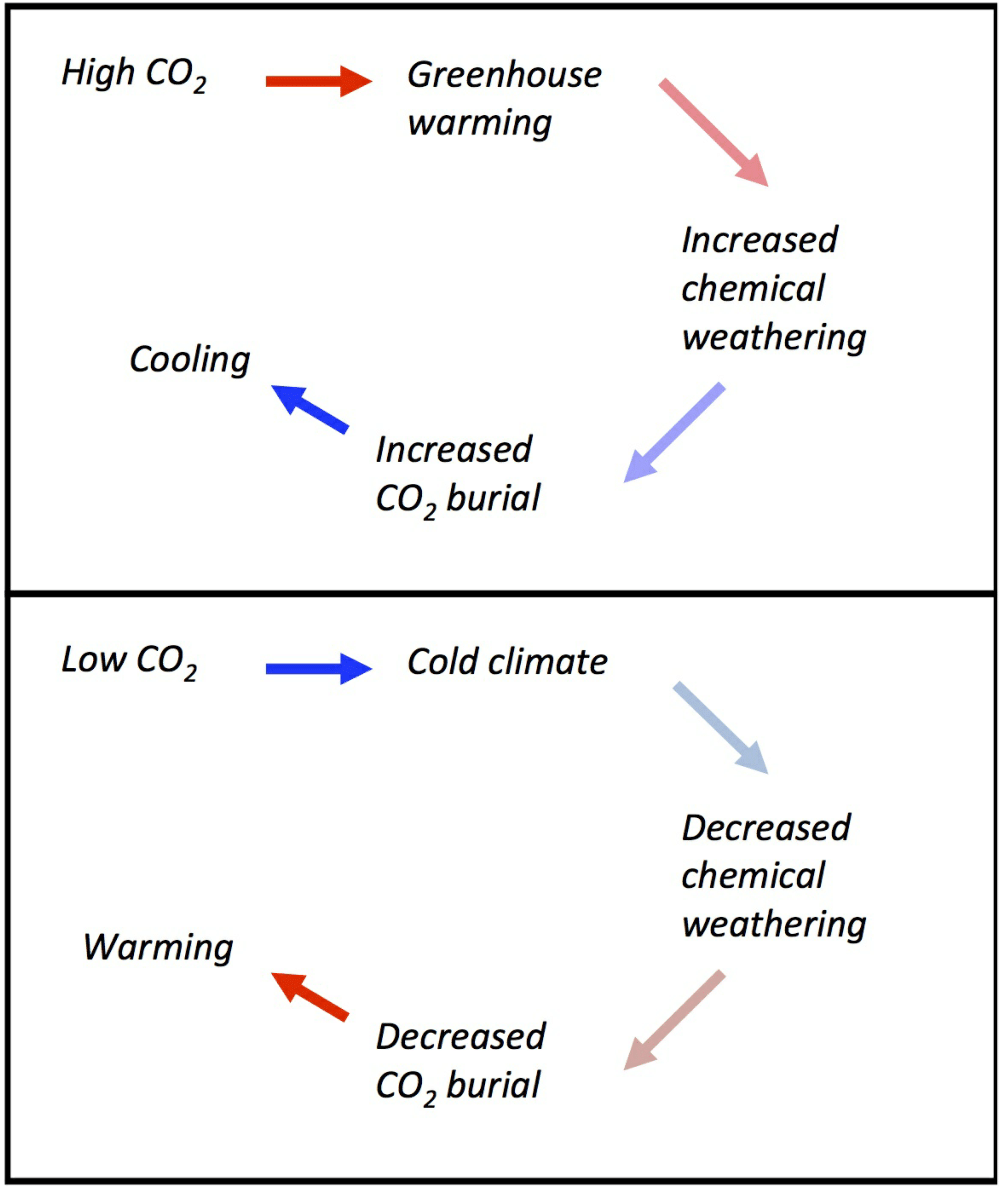

Representation of the Earth’s weathering thermostat that stabilises climate temperatures

Representation of the Earth’s weathering thermostat that stabilises climate temperatures

This is thought to be via temperature control on weathering: if CO2 is added to the atmosphere, temperatures increase. It is, in fact, this same process that is worrying us now through the release of man-made CO2. When temperature increases, weathering increases, simply because chemical reactions occur faster at higher temperatures. More weathering will remove more CO2, eventually leading to cooling. This feedback cycle works the other way round too: less CO2causes colder climates, which means that weathering rates will be lower, allowing CO2 to build up again naturally from volcanic eruptions.

We call this the Earth’s thermostat. As with many Earth sytems, the time periods involved are often beyond human rationalisation. Research suggests that this thermostat rebalances the Earth’s temperature on timescales of 100,000 to 300,000 years – and will eventually be the process that allows the Earth’s climate to recover from the warming and climate change that we are causing.

The Earth has stayed habitable for 4 billion years due to this simple but elegant mechanism operating between temperature, weathering and CO2. And so, to answer the question of why we are here: it’s because nature’s own thermostat has allowed us to be.