They say to err is human, both in the sense of to make mistakes and, more important for our purposes, in the sense of to wander. From the Medieval Romances of Chivalry to the picaresque novel, errancy has been part and parcel of the fictions that have dominated our imaginations for centuries. Our fantasies inevitably surround journeys and strangers. True adventure can only occur by leaving home. The protagonist of the first modern novel, Don Quixote — the 17th-century work of Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes — is just such a wanderer; an economic migrant, a freelance hero, in search of employment for his strong arm, having exhausted the possibilities of a village, whose name the narrator disconcertingly doesn’t wish to remember. Despite heroic glosses, he is in essence a knightly mercenary; his journey, a search for a function, a role, an identity in a society in which he is fading into obscurity, poverty and anachronism.

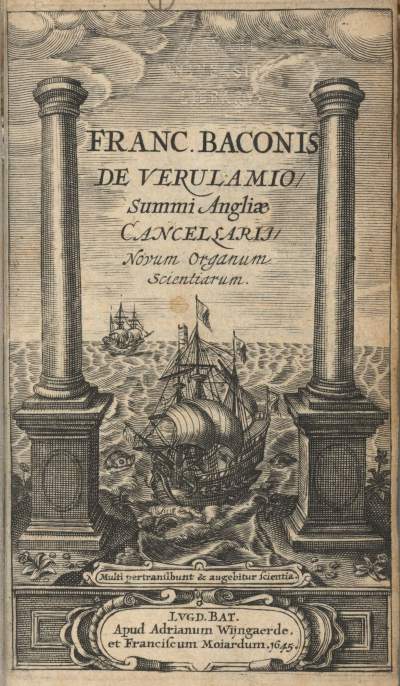

Frontispiece of Francis Bacon’s Novum organum (first published 1620). The Latin translates as ‘Many will travel and knowledge will grow’

Frontispiece of Francis Bacon’s Novum organum (first published 1620). The Latin translates as ‘Many will travel and knowledge will grow’

Displacements of population, like that which Cervantes’ Don Quixote illustrates, are the very matter of our history, so it seems odd that we should be especially surprised by the so-called ‘migrant crisis’, a direct consequence of the last decade’s Western interventions in the Middle East. Our current debates about migrants are not the first time that we have been here.

For thousands of years, thinkers have wrestled with the problem of travel, the ius peregrinandi, the right of pilgrimage, the right to move through and around the world and how this relates to the jurisdictions of the kingdoms and states into which it is divided. If territory came into being through the cartographic ability to measure and so divide space accurately, alongside the legal power to enforce the law within that jurisdiction, then states are an abstraction from land and place, mere ideas that have no relationship to the human experience of geography. Legitimately constituted authority is always a compromise between distinct groups, whether these are stratified socially, ethnically, economically or culturally, as well as a negotiation of the spaces of those groups. The ebb and flow of borders and political groupings constantly pose the question: “Who is a citizen and how does one become one?” Borders cease to have any meaning when no political authority controls the territory they define, a case in point in Syria at the moment. The expelled and thus stateless Iranian Mehran Karimi Nasseri spent eighteen years living at Charles de Gaule airport, a story dramatized in the 1994 film Tombés du ciel and the 2004 Tom Hanks film The Terminal. Who has the right to be where? How and to what extent does who owns or has dominion and jurisdiction over the land, rivers, seas, air and natural resources vitiate or limit this right to travel?

From before its very inception, legality was a principal concern for those who sought to create a Spanish empire in the Americas. In 1493, following Columbus’ first successful trans-Atlantic voyage, Pope Alexander VI issued Inter Caetera, a type of charter (known as a ‘Papal Bull’) that granted all lands one hundred leagues west of the Azores and Cape Verde islands to Spain. Despite the apparent legitimacy lent by Papal support for Spanish dominion in America, its monarchs didn’t rest easy, their consciences tormented by reports of abuses and mistreatment from the so-called New World. A series of commissions and juntas examined the issues around Spanish colonial rule from 1512 to Philip II’s ordinances of 1573. The negative reputation of the Spanish (the Leyenda negra or Black Legend), especially in their role as conquistadors, has been a convenient fig leaf for subsequent empires to herald their superior and more enlightened forms of exploitation, and has obscured the profound questioning and reflection that Spain’s American possessions led to at the time.

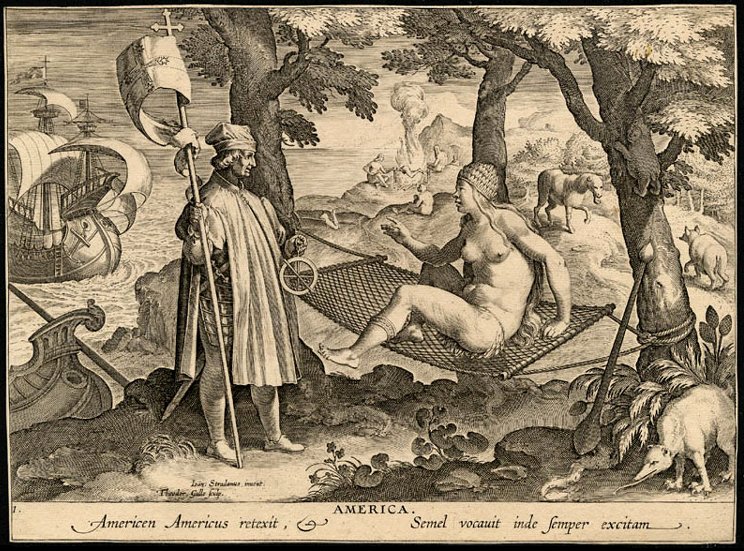

Johannes Stradanus’ engraving of Amerigo Vespucci awakening America (ca. 1630), also known as the Allegory of America

Johannes Stradanus’ engraving of Amerigo Vespucci awakening America (ca. 1630), also known as the Allegory of America

The most significant thinker in the context of the polemic surrounding Spanish possessions in the Americas was the Dominican theologian Francisco de Vitoria, to whom is often traced the origins of international law and whose infamous essay ‘De Indiis’ (Of the Indians), from 1537-8, was suppressed almost immediately by order of the emperor. In his essay, he demolished the major arguments justifying the Spanish conquest of the Americas: from the absence of their dominion, both in the sense of private property and the legitimately constituted power of princes and rulers; the notion that sinners, unbelievers, the irrational, children or madmen were disqualified from exercising authority; the notion that the Emperor or Pope possessed universal jurisdiction over the world; the right of discovery; a refusal to accept Christianity; the free acceptance of Spanish sovereignty; to the notion of it as a gift of God. Vitoria’s first argument in favour is the right to travel and dwell in those countries — the denial of the right of passage was for St Augustine, the early Christian theologian, an injury sufficient to justify war. In support the Saint quoted from the Roman poet Virgil lines that have chilling contemporary echoes:

What men, what monsters, what inhuman race,

What laws, what barbarous customs of the place,

Shut up a desert shore to drowning men,

And drive us to the cruel seas again!

However the nation states of the modern world attempt to control, constrain and contain us within their borders, to regulate our crossings and movements, the freedom to move, to pass port seems intuitively akin to a human right, as Augustine recognised. The freedom to move, to go one way or another, is a fundamental aspect of free will, an exercise of deliberative choice that as early as the 17th century was even perceived to exist in animals. As the 17th century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote, ‘why is the Oxe more made for the Man, than the Man for the Lyon’? Wandering through space, going off course, has a spiritual corollary in the extent to which states can restrict our behaviour, our errancy, and in extreme cases deprive us of our freedom of movement altogether by locking us up in jails.

Five hundred years ago, Francisco de Vitoria’s Salamanca colleague Domingo de Soto wrote a treatise defending the poor. It seemed to him unjust to limit the poor’s right to wander in search of charity, because of a small minority of fraudulent beggars. Perhaps the only difference between the refugee and economic migrant is that the former faces sudden, arbitrary detention and death, while the latter a long, lingering death from hunger, disease or poverty. The economic migrant Don Quixote, the adventurer with whom we began this reflection on people’s right to seek a better place for themselves, is a touchstone for the culture and identity of over 450 million Spanish speakers around the world. He didn’t set out to exploit or conquer others; rather to right wrongs and defend the weak and defenceless. If our unlikely hero had been required to carry identity papers and a work permit, then he would have been obliged to remain at home a mere impoverished hidalgo and the world would be all the poorer a place for it.